In this post, I want to discuss further about muscles functions in the body, particularly the neck muscles. This topic may seem to be quite 'dry and anatomical' for some of you readers out there, but I can guarantee you that it is an important topic for physical and overall health. For me, this is a rare yet cool knowledge anyone can possess, and to know your body better, comes a beneficial advantage to yourself.

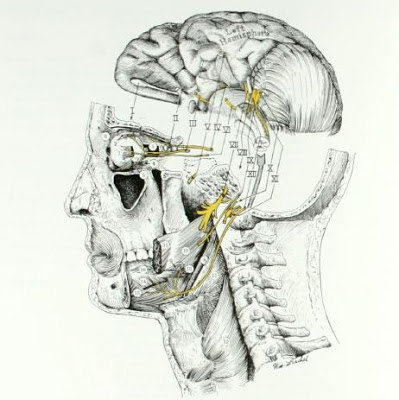

Now, let's get to know our neck much better. The cervical spine and the muscles of the neck form a remarkable structure that provides for movement of the head in all directions, and for stability in various positions. The neck supports the weight of the head in the upright position. For the gymnast who performs a headstand, the neck supports the weight of the body momentarily! The neck is in a position of slight anterior curve, and the upper back is in a position of slight posterior curve.

Now, let's get to know our neck much better. The cervical spine and the muscles of the neck form a remarkable structure that provides for movement of the head in all directions, and for stability in various positions. The neck supports the weight of the head in the upright position. For the gymnast who performs a headstand, the neck supports the weight of the body momentarily! The neck is in a position of slight anterior curve, and the upper back is in a position of slight posterior curve.

In typical faulty posture, the alignment of the head does not change, but the alignment of the neck changes in response to altered upper back positions. If the upper back is straight, the neck will be straight. If the upper back curves posteriorly into a kyphotic position, the neck extension increases correspondingly to the extent that a marked kyphosis may result in a position of full neck extension with the head maintaining a level position. Please have a look at the photos below.

|

| kyphotic posture |

Now, we tend to notice a huge number of people (especially desk jockeys) who suffer from kyphosis @ hunchback posture. A lot of hours in poor sitting position during working hours, driving and also at home watching TV, usage of computers, etc. What about most people in the gym (especially guys) who are obsessed doing bench press and also chronic push up routines? I have met huge amount of guys who would do easily 50-100 reps of push ups every single day. Without correcting the already kyphotic posture, these chronic pushing movements will further aggravate problem, leading to muscular imbalances and even poorer biomechanics. Over developed chest muscle group will lead to tight pectoral major and minor as well, if proper myofascial release is not integrated regularly, and missing out on proper functional pulling movements is critical to avoid muscles imbalances and increased risk of injury.

Bear in mind, chronic problems of the neck may result from faulty posture of the upper back. Along with many attributes, the neck is also vulnerable to stress and serious injury. Occupational or recreational activities may demand positions of the head that result in alignment and muscle imbalance problems.

Bear in mind, chronic problems of the neck may result from faulty posture of the upper back. Along with many attributes, the neck is also vulnerable to stress and serious injury. Occupational or recreational activities may demand positions of the head that result in alignment and muscle imbalance problems.

Emotional stress may cause an acute onset of pain with spasm of the neck muscles. The problem may be only temporary or the stress may be long-standing and result in chronic problems. The appropriate use of massage in the early stages can be an important part of treatment.

A common cause of whiplash injury to the neck is one in which a stopped or very slow-moving vehicle is hit from the rear by a fast-moving vehicle. By the impact, the head is suddenly thrust backward resulting in hyperextension of the neck, followed immediately by a sudden thrust forward resulting in hyperflexion of the neck. Trauma caused by a whiplash may result in temporary and relatively mild symptoms, or may cause severe and long-term problems.

This post presents basic evaluation and treatment procedures in relation to faulty and painful neck conditions. The normal anterior curve of the spine in the cervical region forms a slightly extended position. Cervical spine

extension is movement in the direction of increasing the normal forward curve. It may occur by tilting the head back, bringing the occiput toward the seventh cervical vertebra. It also may occur in sitting or standing by slumping into a round-upper-back, forward-head position, bringing the seventh cervical vertebra toward the occiput.

Cervical spine flexion is movement of the spine in a posterior direction, decreasing the normal anterior curve.

Movement may continue to the point of straightening the cervical spine (e.g the end range of normal flexion), and in some instances, movement may progress to the point that the spine curves convexly backward (e.g a position of mild kyphosis).

It is important to maintain good neck range of motion. We are constantly challenged by the need to turn the head to look sideways or tilt it to look downward to avoid colliding with or tripping over something. Hence, it is advisable to establish and justify a means by which measurements can be taken to determine the range of

motion of the neck in relation to established standards. Various methods have been employed to measure the

range of motion of the cervical spine, such as radiographs, goniometers, electrogoniometers, inclinometers, tape measures, Cervical ROM devices as well as ultrasound. If the upper back is rigid in a position of kyphosis, treatment of the tight neck extensors with massage and gentle stretching may acceptable but still worthwhile.

If the posture of the upper back is habitually faulty but the person is able to assume a normal alignment, efforts should be directed toward maintaining good alignment. Temporary use of a support to help correct faulty posture of the shoulder and upper back may be beneficial as well.

Faulty Head and Neck Positions:

Cervical Spine, Good and Faulty Positions: For the radiograph on the left, the subject sat erect, with the head and upper trunk in good alignment. For the radiograph on the right, the same subject sat in a typically slumped position, with a round upper back and a forward head. As illustrated, the cervical spine is in extension.

Now, let's discuss about neck muscles testing. There will be several variations to test the neck flexors primarily anterior, posterior and anterolateral.

Anterior Neck Flexor

Patient: Supine, with the elbows bent and the hands overhead, resting on the table.

Fixation: Anterior abdominal muscles must be strong enough to give anterior fixation from the thorax to the pelvis before the head can be raised by the neck flexors. If the abdominal muscles are weak, the examiner can provide fixation by exerting firm, downward pressure on the thorax. Children approximately 5 years of age and younger should have fixation of the thorax provided by the examiner.

Test: Flexion of the cervical spine by lifting the head from the table, with the chin depressed and approximated toward the sternum.

Pressure: Against the forehead in a posterior direction.

Weakness: Hyperextension of the cervical spine, resulting in a forward-head position.

Anterolateral Neck Flexor

Patient: Supine, with elbows bent and hands beside the head, resting on table.

Fixation: If the anterior abdominal muscles are weak, the examiner can provide fixation by exerting firm, downward pressure on the thorax.

Test: Anterolateral neck flexion.

Pressure: Against the temporal region of the head in an obliquely posterior direction.

Posterolateral Neck Extensors

Patient: Prone, with elbows bent and hands overhead, resting on the table.

Fixation: None necessary.

Test: Posterolateral neck extension, with the face turned toward the side being tested.

Pressure: Against the posterolateral aspect of the head in an anterolateral direction.

Shortness: The right splenius capitis and left upper trapezius are usually short, along with the sternocleidomastoid, in a left torticollis. The opposite muscles are short in a right torticollis.

Muscle problems associated with pain in the posterior neck are essentially of two types, one associated with

muscle tightness and the other with muscle strain. Symptoms and indications for treatment differ according to

the underlying fault. Both types are quite prevalent. The one associated with muscle tightness usually has a gradual onset of symptoms, whereas the one associated with muscle strain usually has an acute onset.

Neck pain and headaches associated with tightness in the posterior neck muscles are most often found in patients with a forward head and a round upper back. Headaches associated with this muscle tightness are essentially of two types: occipital headache and tension headache.

In a tension headache, in addition to the faulty postural position of the head and neck and the tightness of the posterior neck muscles, an element of stress is also involved. This makes the condition tend to fluctuate with times of increased or decreased stress. In any event, the tight muscles usually respond to treatment that helps these muscles to relax.

Active treatment consists of heat, massage and stretching. The massage should be gentle and relaxing at first, then progress to deeper kneading. Stretching of the tight muscles must be very gradual, using both active and assisted movements. The patient should actively try to stretch the posterior neck muscles by efforts to flatten the cervical spine.

Because the faulty head position is usually compensatory to a thoracic kyphosis, which in turn may result from postural deviations of the low back or pelvis, treatment frequently must begin with correction of the associated faults. Treatment for the neck may need to begin with exercises to strengthen the lower abdominal

muscles and with use of a good abdominal support that permits the patient to assume a better upper back and chest position.

In the next post, I will discuss about work place ergonomics, massages which will help the neck muscles, as well as exercises on how to stretch relevant muscles. Stay tuned.